The #13Percent initiative is sweeping the country with mentions in Governing Magazine and GovExec. We’ll continue to highlight the lack of diversity in local government and hope that you’ll help us raise awareness by sharing the #13Percent initiative with colleagues, on social media, and in conversations.

Early Engagement and Support

By Megan Cohen, Cultural Inclusion Specialist, City of Beaverton

Much like Rafael, I was born in 1989, grew up in the “progressive” Portland, OR, and went to Willamette University. However, as a woman, I can tell you that I have never felt that gender equality was a given.

When I was a teenager, I decided that I wanted to go into politics. I was involved in student government, I worked hard to get good grades and volunteer, and I took every history class that I could, because I thought that was what I needed to do. I had already declared a major in politics when I started college. Much to my surprise, I discovered that my male classmates had a lot of knowledge and connections that I didn’t already have –and I very quickly started to feel that I couldn’t keep up or compete.

When I was a teenager, I decided that I wanted to go into politics. I was involved in student government, I worked hard to get good grades and volunteer, and I took every history class that I could, because I thought that was what I needed to do. I had already declared a major in politics when I started college. Much to my surprise, I discovered that my male classmates had a lot of knowledge and connections that I didn’t already have –and I very quickly started to feel that I couldn’t keep up or compete.

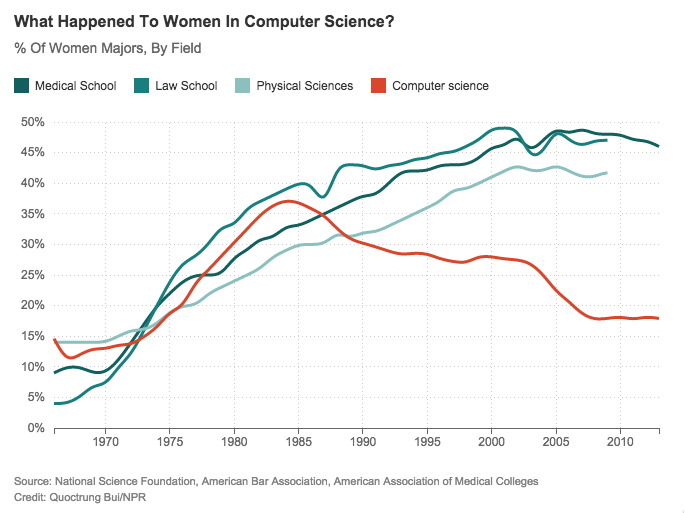

There was an episode on NPR’s Planet Money called “When Women Stopped Coding.” that points out that for decades, the number of women studying computer science was growing faster than the number of men. But, in 1984, “something changed.” For coding, the change came with the rise of personal computer in homes, which were marketed almost entirely to men and boys. It gave them an advantage because they had grown up interacting with computers and coding, and college classes assumed that everyone had a basic level of familiarity.

I found that the same was assumed with politics. When we use language around government, we talk about our “Founding Fathers,” and while the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788, it did not allow  women to vote until the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920. When we talk about the “13 percent,” we need to talk about the historical context behind it. Women were excluded from the foundation of our political system, and it continues to create a different experience for women seeking to become involved in all levels of government. By engaging young women in civics and encouraging them to get involved early, we help prepare them to build upon their experience in both college and their career.

women to vote until the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920. When we talk about the “13 percent,” we need to talk about the historical context behind it. Women were excluded from the foundation of our political system, and it continues to create a different experience for women seeking to become involved in all levels of government. By engaging young women in civics and encouraging them to get involved early, we help prepare them to build upon their experience in both college and their career.

That doesn’t mean that there haven’t been huge, meaningful strides for women in government. What it does mean is that we have a long way to go. I have been told that I need to buy a pants suit for more “professional meetings,” and I have been called “kid” and “girl” in meetings. These are experiences that are different for me, as a woman, than they are for my male coworkers. Oregon is doing better than some, but there is always room for improvement. When we talk about hiring and electing women, we should not ask how they will balance family responsibilities or criticize what they are wearing – because we wouldn’t do that for men.

When thinking about the history that shadows our understanding of women in government and in politics, think about how the first female Supreme Court Justice, Sandra Day O’Connor, was appointed in 1981. Think about how Mia Love (R-UT) just became the first black woman in Congress in 2015. How does this inform public policy? The laws that have been passed? What precedent does it set for the involvement and engagement of women?

There have been many great suggestions for steps moving forward. We need to encourage women (of all backgrounds) to run for office, and managers should mentor subordinates of all genders for professional development within local government. We need to examine our biases around how we think about women leaders and practice inclusion of female colleagues in formal and informal professional gatherings.

There have been many great suggestions for steps moving forward. We need to encourage women (of all backgrounds) to run for office, and managers should mentor subordinates of all genders for professional development within local government. We need to examine our biases around how we think about women leaders and practice inclusion of female colleagues in formal and informal professional gatherings.

We have to begin with engaging women at a young age, rather than assuming that women will feel supported in seeking positions in government on their own. We can also take the basic step of asking the “woman question” – “have women been left out of the conversation?” Whether this question is in regards to a policy being developed, or about staff development offered, it is an important one to pose. More so, we must ask about the implications of doing so. When we talk about #13percent we need to ask not only “how can we get women involved,” but “what will it mean if we don’t?”

We have to begin with engaging women at a young age, rather than assuming that women will feel supported in seeking positions in government on their own. We can also take the basic step of asking the “woman question” – “have women been left out of the conversation?” Whether this question is in regards to a policy being developed, or about staff development offered, it is an important one to pose. More so, we must ask about the implications of doing so. When we talk about #13percent we need to ask not only “how can we get women involved,” but “what will it mean if we don’t?”

Supplemental Reading

- Check out New Leadership Oregon for a great example of encouraging young women to develop their path to leadership: http://www.pdx.edu/womens-leadership/about-new-leadership-oregon

- Girls Inc. Leadership Programs: http://girlsincpnw.org/curriculum/associates-mentor-program/

- And even more great examples nationwide, as well as lots of great ideas for engaging young women (take your daughter to the capitol day?!) http://tag.rutgers.edu/programs-places/

- The fantastic Amy Poehler (Leslie Knope!) leading the way: http://amysmartgirls.com