This post is by ELGL member Andrew Hening.

In 2015, Comedy Central’s The Daily Show aired a brilliant investigative piece called “The Homeless Homed.” In it, correspondent/comedian Hasan Minhaj traveled to Utah to learn more about an initiative in Salt Lake City to end chronic homelessness.

Lloyd Pendleton, the Director of Salt Lake City’s Homeless Task Force, kicks off the interview with an astounding statistic — over a 10-year period, their community reduced long-term chronic homelessness by 72%.

When Minhaj asked how they did it, Pendleton responded,

“We gave homes to homeless people. It’s simple. You give them housing, and you end homelessness.”

Minhaj proceeds to express comedic skepticism that it could actually be so easy, with the satire just reinforcing Lloyd’s point.

Treatment First

Imagine you’re having a heart attack. Your family is terrified. They call 911. An ambulance comes to your house and rushes you to the hospital. When you get to the emergency room, the medics roll you into an operating room. You are on death’s door, and then your doctor says:

“Oh, it’s you. You know, we talked about your heart condition. I told you to start exercising and to eat more fruits and vegetables. Let’s do this. I’m going to discharge you. Go home and eat vegan for six weeks. Also try to jog for 30–60 minutes 3–5 times per week. Once you’ve done that, come back to the emergency, and then we’ll see about treating your heart attack.”

If this response sounds ridiculous, it should. When people are in the middle of a crisis, it is extremely difficult for them to focus on anything but that crisis. Yet for some odd reason, since the emergence of the modern homelessness crisis in the early 1980s, communities have tended to make housing contingent on a “treatment first” basis.

Under “treatment first”, a person experiencing homelessness must demonstrate that they have addressed the underlying causes that led to their homelessness — sobriety, employment, medication compliance.

This is typically a long and gradual process whereby people graduate from emergency shelter to transitional housing to long-term permanent housing, with each step indicating a new level of “self-sufficiency”.

While this model might make intuitive sense, it is deeply flawed. Beyond our emergency room analogy, communities almost always fail to recognize that the overwhelming majority of people who experience homelessness are able to self-resolve their situation in a few short weeks or months.

While people might need a short stay in emergency shelter or some temporary financial assistance, they are already doing everything they need to do to get off the street, and the data suggests people can mostly figure it out on their own.

On the other hand, there is a small minority of people, the chronically homeless, who have a very difficult time self-resolving their homelessness while at the same time generating significant societal costs (healthcare costs, criminal justice involvement, community complaints). When people think of the stereotypical homeless person, most of envision these profoundly vulnerable people.

People experiencing chronic homelessness, by definition, have some type of disabling condition making their situation harder — a mental illness, a substance abuse disorder, a traumatic brain injury.

These disabling conditions make “treatment first” next to impossible because even small program “requirements” can be difficult to meet. The result is that chronically homeless people don’t seek help, become more distrustful, their condition worsens, and then they become even harder to serve.

Because of this vicious feedback loop, in many communities there are people who have been homeless 10, 20, even 40 years.

Housing First

Fortunately, there is another way. As Hasan Minhaj learned from Lloyd Pendleton, the easiest way to break this cycle is to solve the underlying crisis first — a lack of housing.

In the 1990s, Sam Tsembersis piloted a new approach in New York City. Rather than requiring sobriety, med-compliance, or employment, Tsembersis simply offered the “hardest-to-serve” unconditional housing and then provided wraparound support services to work on those underlying challenges.

The “Housing First” model has now been replicated all across the country, and the results have been profound. In community after community, from Salt Lake City, Utah to Bergen County, New Jersey to Marin County, California, Housing First is significantly more effective than Treatment First.

In an early study of Tsemberis’s program, a sample of 100% homeless, 100% mentally ill, and 90% substance dependent people were randomly assigned to either Treatment First or Housing First. Two years later, Housing First had a nearly 200% higher retention rate.

You might think an intervention like this is extremely expensive, but ask yourself, what is the cost of the alternative?

Study after study has shown that people experiencing chronic homelessness, per capita, cost taxpayers $60,000+ per year to remain homeless.

This is because of emergency medical costs, emergency mental health treatment, and criminal justice involvement.

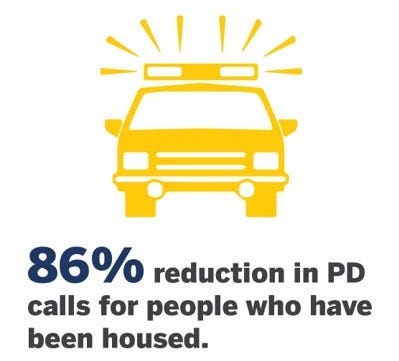

In San Rafael, CA, where I have spent the last six years working, after housing chronically homeless people through Housing First, we saw the following:

By keeping people housed and reducing their public service utilization, even after factoring in rental subsidies and case management support, it can be more than 50% cheaper to actually house people instead of letting them languish on the streets.

Ethically, economically, pragmatically, Housing First is the way to go. In fact, when you consider that the overwhelming majority of people experiencing chronic homelessness are mentally ill following the disastrous implementation of “deinstitutionalization,” in a way Housing First is finally the fulfillment of community-based mental health treatment for the most seriously mentally ill.